|

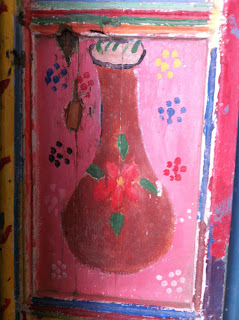

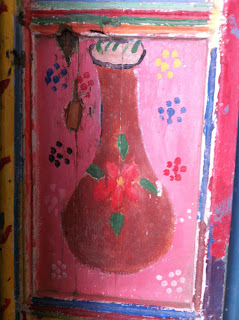

| Naseer's homeless doors project; these are doors gathered from demoilshed homes by IDF soldiers over the past 8 years. He invites Nablusi community members to come and paint them any way they like.. These doors are painted by children and adults. Sometimes he reinstalls them in rebuilt homes. They are mostly opportunities for community members to express something about their experience living under occupation. |

Among the many things that amazed me about being with Palestinian people in the West Bank is their amazing resilience and creativity in the face of oppressive, harsh and challenging circumstances. These circumstances appear to differ from week to week, month to month, and in the case of particular years when they faced excessive force and violence during the second intifada (years 2000-2003). One thing I heard over and over is that the punishment and force they experience either at the checkpoints or at demonstrations quite simply depends on the "mood of the soldiers." What I found in many conversations, observations, and interactions with Palestinians from the West Bank is their determination not only to survive (and survival is the operative word here), but also their desire to build some kind of viable society even while they feel they're under attack.

What I mean by being under attack is this:

many Palestinians feel the occupation leaves them in a state of constant insecurity--they have no state, no borders, no control over their lives. Everything is governed by Israeli occupation (the flow of goods, the flow of people, their ability to build, to expand, to have contact with the outside world, their ability to represent themselves and their interests, their ability to plan for their future, their ability to protect themselves and their children from violence, and their ability to provide resources for a viable state system that ensures a kind of continous history.) I will probably repeat this same idea while I continue to digest this trip and write this blog. But I could hear this refrain over and over--stated perhaps differently, but unequivocally and in some kind of unison:

The occupation (from 1948 Nakba (the catastrophe) to the the 1967 Naksa (the set back) determines everything about the past, present and future of Palestinian life. They seem themselves as a people controlled by a state that both denies their existence and wants to erase their existence. This has a kind of historical resonance, doesn't it?

Faced with this kind of marginalizing existence, I want to talk about the positive things I observed in the ways that the people of Palestine are coping. Because, even while I found myself dismayed, troubled and outraged at how they're living with the occupation, I also found their ability to adapt and innovate remarkable and inspiring. One example of this was when we went to the West Bank city of Nablus in the northern part of the West Bank. Nablus is an old city and quite large. It's a city which was historically known for its olive production---soap and olive oil, but especially soap. We got a tour of the city from both the old quarry high on a hillside, as well as from down in the oldest section of the city, with a man named Naseer Arafat (no relation to the former chairman of the PLO and the first president of the Palestinian Authority). Naseer is an architect and cultural preservationist by profession so he knows a lot about the city, and the many hidden treasures within it. He also knows a lot about what happened to Nablus under the occupation. He told us that in 2007, Nablus had 307 days under curfew; in 2002 they were under curfew almost entirely the whole year. What that means is that the Israeli military literally camped out in the city, monitored people's movements, and allowed no cars and people in and out of the checkpoint that leads into the city without permission. It also meant that people were severely restricted inside the city and were allowed three hours a week to go out and do their shopping. He described this in a way that seemed hard to believe, because we saw bustling streets and commerce all over the town. But he said the checkpoint had only been opened recently and people felt like they could breathe again. (interesting article featuring Naseer: http://electronicintifada.net/content/breathing-life-nablus/5693).

|

| Outside Naseer's office in the old city of Nablus. These doors he's collected from demolished Palestinian homes for his door project. |

|

|

|

|

Curfews are a regular part of Nablus life for two important reasons; they've been a stronghold of resistance both against the occupation and against the settlers who have attacked the surrounding villages around Nablus in provocation for taking land and claiming some kind of biblical rights to it. The city also contains one of several Jewish holy sites. "Joseph's tomb" which settlers often aggressively seek out and invade often in large numbers at night with the escort of IDF soldiers--assuming it is their right to worship there even if it means trampling on Palestinian rights and land. This is how the settlers are not to be underestimated. In a way, they're doing the dirty work of provoking conflict, that almost always seems protected by the Israeli military, which then becomes a kind of pretext for further occupation and control of Palesitnian land through military, road blocks, and inevitably the Separation Wall which imprisons Palestinians on their own land and also breaks up the Palestinian community into enclaves or bantustans. I'll post a map later--but the settler/colonizer paradigm is so similar to what happened to Native Americans!

Anyway, back to Nasser and the great work he's doing. Because Nasser is an architect, he's been instrumental in preserving buildings in the old city, rebuilding areas of Nablus which have been demolished by the Israeli military during its curfews and military incursions, as well as for example discovering historical links between particular eras and construction. He gave us a slide show in which he traced the many people who traveled and settled Nablus --including the Canaanites, the Romans, who left their architectural legacy here before the more recent Jewish/Arab populations. He also told us about the Samaritans (the oldest known Jewish community continuously living in Palestine). The Samaritans see themselves as the original Jews of the tribes of Israel and though there are only about 300 of them living in the Nablus area, Nasser described that they were on good terms with the Muslim/Arab community. They have both attempted to remain neutral and at times helped to mediate conflict in Nablus. I asked Nasser a few questions, and he generously answered. I continue to be fascninated by this community. For more about them, I recommend starting with these articles:

http://www.livius.org/saa-san/samaria/samaritans.htm;

http://www.zajel.org/article_view.asp?newsID=4429&cat=18. They have a unique position in Israeli society---and they reject many aspects of modern Judaism, seeing the faith having been altered by Jews in diaspora and those seeking a Zionist reinterpretation of it in the modern state of Israel.

|

| Naseer shows us around his cultural heritage center and points out th | e old soap factory contained within it. |

|

|

Nasseer's work seems encompass two areas--working on cultural preservation and renovation within the city, and also working to provide cultural outlets for Palestinians living under occupation. His family used to run an olive soap-making factory in Nablus (at one point there were around 35 of them), today there are only a handful, and he has turned the soapmaking factory which is in the heart of the old city of Nablus into a cultural museum and art center. His center has been attacked and bombed four times by the IDF soldiers because he is a high-profile person in Nablus. He has rebuilt it each time, and has tried to keep it open as a cultural center. The last demolition, after which he rebuilt his office, he kept the original door post-destruction (see below), in order to show people what happens to Palestinian doors in a regular way. He also kept the sign in the old city that has been shot at by IDF soldiers (see also below). The Cultural Center which was his father/grandfather's old soap factory shows all the old tools for making soap. There is an underground well (I am not sure it is a well--some kind of storage area for the oil which is then mixed and cooked with water and a sodium compound. See pictures below.

|

| Inside one of Nablus's few remaining and still functioning Turkish baths. |

|

| The famous knafe maker of Nablus who boasted the Guiness Book of World Records largest tray of Knafe after the Israeli curfew of 307 days was lifted in Nablus! |

Because he is a historian of the old city, and his work as a cultural preservationist, it is, by necessity, political. He identifies all the ways that the different cultural influences have passed through this ancient city--the Canaanites, the Romans, the Jews (and especially the Samaritan Jews who only recognize the first five books of the Bible as legitimate), the Muslim Arabs, the Seljuks, the Ottomans, and within the last millenia, and a half,-the Arab community that largely resides there today--Palestinians. In addition to giving us the view of the entire city from a point where the Romans used to quarry for stone (and which is below an Israeli military base high in the mountains) he pointed out the religious sites to us--the churches, mosques, the mountain where the Samaritans gather for the sacrifice, even the Turkish baths left over from Ottoman times. He doesn't seem to privelege any group, but rather is interested in the idea of Nablus as a cultural nexus, and the ways that his job as cultural preservationist is to acknowledge all these influences, and to resist attempts to erase or homogenize that history. He took us to the old mosque in town, where he told us he had done some refurbishing of it with the community's help. Naseer was clearly a well-respected figure in the community. Everyone in the old city, the souk knew him, and greeted him warmly. At the end of the day, he took us to Nablus's famous knafe factory (knafe is a kind of Palestinian struedel made with cheese and syrup and it's delicious). After the curfew was lifted, Nablus boasted the largest tray of knafe in the world. Here is the famous knafe-maker of Nablus! (see above).

|

| One of the panels of a door painted by a child. |

Naseer was a delightful man. He was so warm and good humored, and spoke about the resilience of the Nablusi community over and over again. He made jokes, but also spoke in serious tones about what the occupation has done to traumatize members of this community. He told us about his youngest child, a son, now aged five, whose first word even before "mamma" and "baba" was "tank." He said, his child was raised in the atmosphere of occupation and it was only recently that he could sleep with the light off and without the plastic pistols he had surrounding his bed. "The trauma of occupation, the violence, home demolitions, the gunfire,"he told us, "that has scarred us, and left an indelible mark on our children. This is why they need art--to help them process and release this pain." Naseer showed us the ceramic studio in the Cultural Heritage Center where he holds classes for children and adults throughout the year. He also has a library within the cultural center for kids and adults. Anyone can come and use books, read there, take books out. He's always looking for book donations as well. The art projects and classes he makes available for people are very popular--he holds classes on a regular basis, and inside the center he had an art project hanging up that was a collaboration between Stavanger, Norway and Nablus, Palestine artists (Stavanger is Nablus's sister city). This kind of international collaboration around art--is something I wish we could do more of with Palestinians. "The people, young and old of Nablus, come and make art here," he says, "because it helps us all remember our humanity, remember our stories, find our lives."

No comments:

Post a Comment